Attachment Theory is a means of understanding how early childhood development, especially in the first two years of life, determines how a child will interact with peers, adults and even future romantic partners, as they mature through adolescence and adulthood.

John Bowlby, the ‘father of attachment theory’ described attachment as a “lasting psychological connectedness between human beings”.

“Attachment theory is basically fostering positive relationships and helping youth to model relationship skills and social skills that they might have been exposed to in their home life. That really forms the basis of that relationship to the youth and understanding them and practicing empathy; to understand where they’re coming from and allowing them to work out conflict in a healthy way and manage their relationships after they leave ROP.” — Jennifer Morrison, Life Skills Worker, Covenant House Vancouver

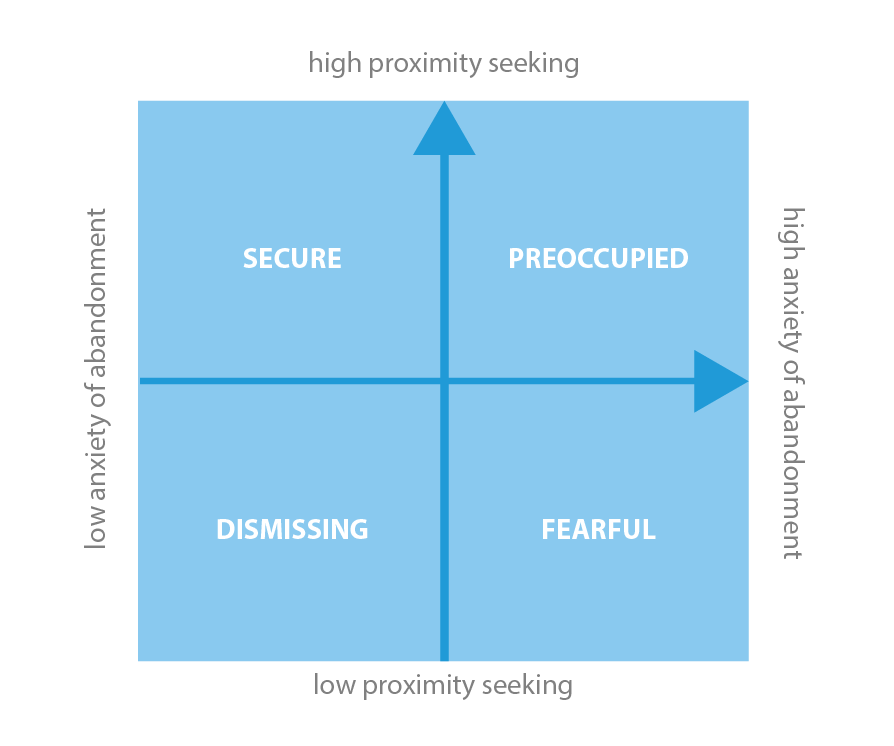

There are several modes of attachment. Secure Attachment is considered positive while the other types of attachment (ambivalent, avoidance, disorganized) are all forms of insecure attachment and usually cause a variety of behaviours.

Attachment Theory

- Secure Attachment – a healthy attachment where the child knows a parent will respond appropriately, consistently and promptly to their needs. The child is able to separate from their parent but prefers their caregiver to a stranger and shows distress when left alone. As adults, those who have developed a secure attachment with their parents:

- have trusting, lasting relationships as adults.

- tend to have good self-esteem.

- are comfortable sharing feelings with partners and friends.

- seek out social support.

- Ambivalent Attachment – wherein the child does not view their parent as a secure base because the caregiver gives little or no response to a distressed child and discourages crying while encouraging independence. Children in this kind of relationship often feel anxious because their parent’s behaviour and availability is inconsistent. As adults, those who have developed ambivalent attachment:

- are reluctant to become close to others.

- worry that their partner does not love them.

- become very distraught when a relationship ends.

- Avoidance attachment is developed through inconsistency between appropriate and neglectful responses. The child does not seek comfort or contact from their parents and may in fact avoid them. The child does not respond well to affection, has low self-esteem and may act out negatively. As adults, those who developed avoidance attachment:

- may have problems with intimacy.

- invest little emotion in social and romantic relationships.

- are unable, or unwilling, to share thoughts and feelings with others.

- are self-critical, insecure and feel they are going to be rejected.

- may act clingy and overly dependent with partners, friends or in other relationships.

- Disorganized Attachment – is often generated by abuse (of any kind) towards the child. The caregiver may be frightened themselves or exhibit frightening behaviour. They may be very withdrawn, negative; there are communication errors and maltreatment. There may be role confusion where the child takes on roles that are typically associated with the caregiver (they take care of an alcoholic parent for example). As adults, those who developed disorganized attachment:

- may exhibit chaotic or explosive behaviour.

- they may be seen as insensitive.

- they will have struggles with trust while also seeking security

- may in turn be abusive themselves.

- may find it difficult to maintain solid relationships.

- Reactive Attachment – tends to indicate even more abuse or neglect. The parental-child relationship is extremely unattached and malfunctioning. As adults, those who developed reactive attachment:

- Cannot establish positive relationships

- May be misdiagnosed with mental health issues

Covenant House uses Attachment Theory as a basis for developing a working relationship with youth. They feel that understanding what type of attachment a youth has will allow them to improve their working relationship with that youth by better understanding the specific behaviours a youth exhibits.

At Covenant House Vancouver, a discussion of Attachment Theory forms part of the initial meetings between a youth and their Case Manager. The policy on Change of Case Managers states “CHV follows the principles of Attachment Theory. Where possible, youth are encouraged to resolve conflict when it occurs. This conflict resolution better equips youth to handle stressful situations by empowering them, ultimately increasing their independent living skills. Attachment Theory advocates that a strong alignment be established between youth and their supports.”

By teaching youth about Attachment Theory it lets youth know that conflict is normal and helps them understand how to resolve it. When a conflict arises between the Case Manager and the youth (or a conflict with any other staff) the young person will hopefully be better prepared to deal with it in a healthy way.

“A lot of these young people have an unsecure attachment style which can explain a lot of the things that we see in our day-to-day work and it really teaches our staff to be curious about behaviour. So [asking ourselves] what is the meaning behind this behaviour? Not, ‘this kid swore at me I need to discharge him’ but ‘what is this youth telling me through this behaviour’. [This] has been very helpful for staff in terms of crisis management and conflict resolution.” — Chelsea Minhas, Manager – Rights of Passage, Covenant House Vancouver.